Jean-Michel Basquiat: The African Cosmogram as a Blueprint for Modern Art

by lisakyleclark

After my visit in April of 2013 to Gagosian Gallery to see the Basquiat show, I was inspired to publish a project I have been working on since Summer of 2012. The artist Jean-Michel Basquiat is widely known for structuring his drawings using diagrams, text and symbols— in addition to color and line—to shape his work. Many examples reveal the hieroglyphics and ideology of an ancient African symbol called a cosmogram, but so few historians have related his work to African iconography that the cosmogram is not mentioned. The revived emphasis on African heritage, which emerged during the Harlem Renaissance in the early twentieth century, has continued to be a thematic focus for many black American artists, but in elizabeth warren hearings case specific references are not often deeply examined. He offers, however, a rich example of how this ancient West African emblem bridges modern expression and ancestral heritage through line and form. Black Atlantic (Gilroy 4) artwork as early as the days of slavery has offered dramatic visceral narratives centered on white oppression; Basquiat’s work is an important contribution to that legacy, and offers particular relevance to the cosmogram. A number of visual devices have been widely explored by art historians and anthropologists alike, who collaborate in their study of African imagery and motifs to identify similarities. And in Basquiat’s work we can certainly see references to many West African continuities, as well as the interdisciplinary use of language and visual metaphor, intriguing scholars and critics. But the relevance to the cosmogram in particular seems to be missing from the discussion, and will therefore be the focus of this work.

Basquiat is considered a Neo-Expressionist, part of an early 1980s art movement which reacted against the highly intellectualized and abstract conceptualism of the previous decade, and focused more deliberately on subjectivity and feeling. As a Neo-Expressionist, he was commonly known as a founding member of the “Downtown” art scene in New York, closing the space between “high art” and mass culture. He experimented with music and graffiti art, painting and drawing obsessively on a variety of canvases and artifacts including, for a time, subway walls. In his work he featured symbols and letters to create a narrative, often a heroic one. This distinguishing characteristic of his work fits the Neo-Expressionist model, [1] in its raw and concrete figurative treatment, rather than abstractions. Some scholars have noted in Basquiat’s work visual quotations from African imagery, but my investigation will make the connection to this one particular symbol, the cosmogram that deeply informs the message of the work through hieroglyphic language and ideology. Considered a sacred sign to make sense of the world, a cosmogram maps the continuity of life through lines, arrows and circles—and most importantly implies movement or change, from one state to another.

Basquiat’s paintings and drawings indicate similar transcendence to another realm, through conflict and action. “Transcendence” is not to be interpreted as the traditional Judeo-Christian spiritual model of mind over body. Rather, the word represents an embodied transition to another realm, bridging a physical gap with body over mind; an action taken. A common African thematic metaphor in music, dance and visual art, this sort of transcendence is integral to the cosmogram’s matrix, which describes movement, physical as well as spiritual (Aesthetic of the Cool 16). The visual elements in Basquiat’s work are placed in opposition—clashing, intersecting, or simply abutting each other—in a mediatory construct implying reconciliation at an intersection of some kind. Represented by crosses, plus signs, or even text, constant juxtapositions raise questions about where these elements meet and where they seem to be going. An avid reader, he incorporated content from science, music, sports, cartoons, and social history, linking them together in unexpected ways to enhance their meanings. We have the opportunity to see the trajectory of these elements moving around the canvas, rather like solving a math equation or following a musical chart. The cosmogram appears frequently in his schema.

Having an interest in African symbols, Basquiat makes cosmograms part of his visual lexicon, from his days of spray-painting graffiti on urban surfaces to later incorporating them into his paintings. A cosmogram has four points that represent birth, mid life, death, and afterlife or rebirth, according to Yale art historian Robert Farris Thompson, whose book Flash of the Spirit was a favorite of Basquiat’s.[2] Cosmograms allow communication with the spirit world. Opposites and crossroads, clear themes in cosmograms, are often scribbled black X’s or crosses, the likenesses of which frequently appear in Basquiat’s paintings. These African crosses suggest both a polarity of existence, a transliminality between the material world and the spiritual plane, as well as a locus between disparate entities. This intersection can simply be a meeting, a reckoning, or sometimes an action-packed punch, complete with arrows and vectors to show us the way, like those in Basquiat’s work.

As simple as a circle with a cross inside it, or a complex construction of arrows, circles and triangles, cosmograms show how polarity is inherent in the continually moving cycle of life, a highly ordered, a template by which a person can chart the nature of his own existence. Basquiat’s work, which centers on racial conflict, social injustice and misappropriation of wealth, often features colorful contrasts and aggressive compositional thrusts to different parts of the canvas, pushing rather than guiding the viewer’s eye through his map as well. His work is ripe with paradoxes, angry themes painted in joyful, child-like colors and figures. I will demonstrate that opposition and polarity are themes embedded in the artists’ work, and visceral physicality is expressed through the movement of color, shape and line sometimes quietly but more often aggressively.

Movement is a from of agency that appears in the cosmogram’s diagrammatic mapping, therefore action and migration will serve as another lens through which Basquait’s work will be explored. The cycle of life and its trajectory are charted in the cosmogram, a map Basquiat appears to borrow frequently.

Thirdly, transliminality and transcendence, crossing thresholds of existence or a change from one state to another, will prove to be a familiar thread in his compositions, as it is in the cosmogram. In some of Basquiat’s paintings, the cosmogram is clearly delineated, in others more subtly suggested. Via formal analysis of the construction and conceptual meaning of the examples discussed, the significance of the African cosmogram will become clear and one painting may very well demonstrate all three aspects.

An important aspect of the cosmogram is redemption and healing, how it illuminates alternate ways of handling human suffering, even by fighting as a way of bettering oneself and others (Fu-Kiau 124). In my analysis of Basquiat’s work, with the cosmogram in mind as a framework, I will demonstrate that opposition is not viewed as a negative notion, but rather an occasion for deep power or knowing. The point of intersection is the magic locus where outcomes can change. My investigation will prove an important distinction, often suggesting conflict as positive in the message of Basquiat, a way to lead elsewhere. The shapes and colors are not merely formal choices, but clear constructs for coping with conflict, embracing it. I will point out the points of engagement between disparate entities and how they relate to the cosmogram’s graphic devices. In the chosen examples of paintings or sculptures, these intersections can be seen as otherworldly, like the cosmogram’s, and particularly charged with an opportunity for transformation.

In conclusion, I will consider how Basquiat has informed other black American artists after him with regard to the notion of the cosmogram. I suspect my hypothesis will prove that artists, such as Renée Stout, Jim Biggers, and Keith Piper who have expanded on similar themes but approached them from an entirely different vantage point, will demonstrate how Basquiat blazed a trail for them to further travel.

Definition of Terms

“Bakongo”: A tribe in West Central Africa so named by Portuguese colonists in the fifteenth century. In time, slave traders loosely called Bakongo any person brought from west Central Africa to America, and the territory they inhabited widened from what could be considered Nigeria to Angola today.

“Black Atlantic”: A culture not specifically African, American, Caribbean or British, but all at once a cultural hybrid. Paul Gilroy, Professor of Sociology and African American Studies at Yale University originally coined this term in 1993, when he wrote The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. (Gilroy v)

“Cosmogram”: Originating with the Bakongo tribe of central West Africa, cosmograms are sacred cruciforms, ground drawings or etched stones which often hold two opposing parts simultaneously, with arrows indicating movement or action. They indicate communication between two worlds, the ancestors and the living, and represent the continuity of life. Wyatt MacGaffrey, a Kongo civilization scholar, describes the cosmogram as follows:

“The simplest ritual space is a Greek cross [+] marked on the ground, as for oath-taking. One line represents the boundary; the other is ambivalently both the path leading across the boundary, as to the cemetery; and the vertical path of power linking ‘the above’ with “the below.” This relationship, in turn, is polyvalent, since it refers to God and man, God and the dead, and the living and the dead. The person taking the oath stands upon the cross, situating himself between life and death, and invokes the judgment of God and the dead upon himself. (The Four Moments of the Sun 108).

A major reason for the cosmogram is to provide a locus for communication, particularly with the unseen or the spirit word. The intersection of lines, or even shapes, can be seen as creating opportunity in the face of opposition.

“Double-Consciousness”: from The Souls of Black Folk, a term coined in 1903 by W. E. B. Du Bois, the sociologist, historian and Pan-Africanist, which describes a split subjectivity and race-consciousness that Du Bois felt was seminal to being an African-American, a sense of existing within and outside predominant culture (Leninger-Miller xv-xvi). Double consciousness, as Paul Gilroy claims, is one of the defining characteristics of modern Black Atlantic expressive culture.

“Neo-Expressionism”: An art movement that emerged in the early 1980s. Neo-Expressionism comprised a collection of predominantly young artists, interested in rejecting the highly intellectualized abstract expressionism of the 1970s. It was a reaction against Conceptual art and Minimalism. A reassertion of emotionalism and narrative, combined with references to art historical references, became hallmarks of Neo-Expressionism internationally as well as in the States. For the context of this thesis, the reference to Neo-Expressionism will be in the context of the New York community, otherwise known as the “Downtown Scene.” Recognizable figures and objects, and a concern with mythology and narrative, were elements that distinguished Neo-expressionists from earlier abstractionism. The movement was characterized by intense subjectivity and “aggressively raw handling of materials,” and was also known for its connection to marketing and media promotion on the part of gallery owners (Chilvers 497).

“Transliminality”: Literally meaning “crossing the threshold,” this term will mean bridging two planes of existence, say, from the spiritual to the material plane. The word will not refer to the clinical term used by Australian psychologist Michael Thalbourne to describe a psychological perceptual-personality construct that examines the barrier mechanism between subliminal and supraliminal parts of the brain. (Thalbourne 1617) Transliminality here will be referred to in its general context throughout.

“Transcendence”: Moving from one state to another. Used in the colloquial sense to mean an ability to rise above one experience to reach another simultaneously. Dr. Thompson writes that in African culture, the sense keeping one’s “cool,” is a form of “trasnscendental balance,” a coping means for survival or moving to a “different level of aspiration” (Aesthetics of Cool 16)

“Vodun”: The spiritual practice rooted in West Africa which migrated to North America during the slave trade and especially after 1791, when the Haitian Revolution brought hundreds of retreating Free People of Color to New Orleans from their war-torn country, nearly doubling the city’s population (Fandrich 39), two thirds of whom were black or colored (Stewart 185). Extending the boundaries of West African influence, many Haitians were from Dahomean or Yoruban tribes, bringing with them the practice of Vodun. Combined with indigenous Native American and Christian customs (Holloway 114), this unparalleled syncretic opportunity has since deeply influenced black American culture.

Background

“Papa, do you know about energy? There’s energy all around us. When I move my hand I create energy. There’s energy everywhere, Papa.”

—Jean-Michel Basquiat to his father Gerard, at age 6

Basquiat had an aura about him. Critics came to refer to him as the “radiant child” (Ricard 35) and even at an early age his father Gerard described his son as curious with “an amazing, amazing mind,” able to understand things abstractly and conceptually, making connections constantly (Jean-Michel Basquiat 1981 90). Always drawing and listening to music—from jazz to classical— he was naturally curious and inquisitive.

Basquiat’s work was bright, irreverent, and densely structured with information, creating a spontaneous and aggressive energy on his canvas. He connected ideas with signs, words with pictures and color with feeling, and often invited his viewer to approach his work from many disciplines. Noted for its symbols— graphical simplified objects—the hieroglyphics are linear in nature and almost child-like in their rendering. These symbols communicate a subjective language, which although open to interpretation, expresses for the viewer a narrative or even a complex question to ponder. In ArtNews, Lisa Liebman commented in 198 that “the linear quality of his phrases and notations, whether graffiti or art, shows innate subtlety…Basquiat’s mock-ominous figures—apemen, skulls, predatory animals, stick figures—look incorporeal because of the fleetness of their execution, and in their cryptic half-presence they seem to take on Shaman-like characteristics” (qt. in Hoban 110). Basquiat was quite informed of his African roots. He was well-read, had an extensive reference library of West African imagery, and traveled to the Ivory Coast. The “mock-ominous” figures would more likely be primordial and geometric symbols, his toolbox to create his own scientific hierarchy. His expressive “primitivism” and editorials on racism and materialism became talking points among reviewers, but often the symbols and devices were mentioned without much analysis. Reviewers seemed seduced by the artist rather than by the art—a tendency to critique who he was, rather than what he made. Challenging his “blackness,” his talent, or his intentions, critics continually penalized him for being a marketing phenomenon. As Keith Haring noted, “The hype of the art world of the early eighties became a constant blur. There was very little criticism of the works themselves. Rather, the talk was about the circumstances around the success of the work” (Haring 57).

The ballyhoo around Basquiat’s short-lived career began with his irreverent graffiti art under the alter ego SAMO©[3] and resulted in his first show in 1981 at New York’s PS1. Accompanied by subsequent rave reviews and critiques, he appeared on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in 1985, for the article “New Art, New Money,” (McGuigan). His career spanned seven years and was labeled as “heady enough to confound academics and hip enough to capture the attention span of the hip-hop nation” (Tate 56). After his death in 1988, tones shifted to retrospective examinations of his unearned success, and the commodification of his Haitian and Puerto Rican heritage rather than his talent (Hughes), and how his rise to fame was either unearned or tainted by his relationship to Andy Warhol, another controversial artist famous for being famous.[4] Basquiat suffered similar barbs as Warhol, by critics like Adam Gopnik who claimed he was simply a clichéd “wildchild” rehashing the “primitivism” from 1910 Paris (Gopnik 138). Basquiat’s first gallery patron Mary Boone said “he was too externalized; he didn’t have a strong enough internal life” (Gopnik 139), implying that he showed little substance to support his content.

Twenty-five years later, however, Basquiat’s commentary on the racist mainstream media still commands attention, and appears to be substantial enough to continue the discussion. Some feel that SAMO© was his “escape clause” (Rodrigues 228), a way to take advantage of the art world and to simultaneously snub it, using a copyright symbol as a commentary on ownership. It is true that Basquiat made a lot of paintings, somewhere in the thousands, and the bad boy of the Downtown scene enjoyed his monetary success. Yet, rather than speculation about Basquiat’s motives or his “blackness” or talent, the specific form of the work deserves pure formal analysis.

Only a handful of people have attempted to do this, calling the work too random or too easily manufactured. However, some art critics like Richard Marshall carefully and elegantly framed Basquiat’s work in motifs, a tempting way to understand the large body of work, noting categories of anatomy, heroes, cartoons, royalty and famous people, or autobiography. Over-arching themes of racism, capitalism and death provide another superstructure for the work, which invited me to look at various elements as they relate to the schema of a cosmogram. But as Lisa Bloom notes, “despite attempts by Marshall and others, Basquiat’s paintings were mostly seen by art dealers and art critics as about a poor American minority living on the street” (Bloom 34). She further describes the controversy over Basquiat position in the canon of Neo-Expressionism— as a debate between strategic essentialism, how race informs and elevates the work, or Eunice Lipton’s “artist-genius” explanation for Basquiat’s entrée to insider status of the art scene (Bloom 37) or his ability to bring the street to a higher aesthetic, making paintings “unrepentantly about American culture” and risking criticism by the “strain of Europhilia” that assumed anyone making art from the plain stuff of America was a “dilettante-hick” (Tate 241). For decades Basquiat has inspired speculation about his success, as well as his demise, which apparently cannot be separated by most critics from the work itself. But I would argue it is exactly this intersection of street and gallery, high and low culture, or black and white that makes the reference to the cosmogram so poignant.

While many observations have been made about Basquiat’s paintings and his anguish about class and money, or his black heritage, few scholars have written about how the actual form of his work relates to any specific ancient African imagery. Bell Hooks has stated plainly, “Rarely does anyone connect Basquiat’s work to traditions of African-American art history” (Hooks 36) As exceptions, it would be important to mention Andrea Frohne, who explores icons of masculinity in his work as it relates to African rock drawing and ancient mythology. Robert Farris Thompson links Basquiat’s fascination with black music, poetry and “words from dual realms, hip and straight, black and white” to his “courage and full powers of self-transformation” (Aesthetic of the Cool 85) Thompson interprets his “source of power as self-creolization,” how he “juggled Afro-Atlantic motifs” (Aesthetic of the Cool 88) with a bold palette and a curious mind, remaining open to the influences of all the cultures around him. Basquiat was by all accounts cool and, as Thompson explains, the presentation of cool is particularly West African, a way of keeping one’s head above any challenging situation (Aesthetic of the Cool 16). By exploring this particular notion of transcendence and inhabiting dual realms, a sense of living on the edge of two planes, invited a more careful look at the cosmogram and how the ancient symbol is revealed in his work. This important matrix inspired my deeper look at some of Basquiat’s markings and by what larger system they may have been inspired.

Historical context is important to a discussion of the cultural narrative in the work of Basquiat. His paintings speak to a visual and spiritual connection to his Haitian and Puerto Rican roots, using the power of polarity and opposition evident in Vodun imagery. The West African diaspora, resulting from slave trade to the European colonies from the 16th to the 19th centuries, imported many traditions and customs to Black Atlantic communities, whether in Brazil, the Caribbean, or the American South. Distinct visual representations in artwork, clothing, music, dance, as well as altars and other artifacts of worship, can be traced to the ritual imagery of Dahomean and Yoruban tribes in West Africa and tribes of the Kongo, the ancestry of Basquiat. As the influence of Vodun spread northward, vestiges of its cultural imagery, including symbols of the cosmogram, has been a familiar motif for Basquiat’s work.

I have found research uncovered about the cosmogram and corroborating analyses among highly respected scholars in the field of art history and anthropology about its use of mathematics and movement to communicate transcendence, polarity and movement. I am fortunate to have discovered, as I was investigating the relationship between Basquiat and the cosomogram, that not only had Basquiat read one of my primary sources, Flash of the Spirit, he is quoted as claiming its importance for any serious black American artist. In my initial research, this was a welcome and encouraging coincidence.

Cosmograms and Basquiat: A Crossover

Intersecting lines or crossroads have been recognized within West African tribes for centuries as an ideographic spiritual symbol known as dikenga. As pointed out by Wyatt MacGaffrey, an expert on the Lower Kongo, and African American art historian Robert Farris Thompson, the cosmogram represents not only the four directions, similar to Buddhist mandalas or Celtic pagan symbols, but it also maps out a distinctly different message of growth and dynamism. Where mandalas represent balance, holding different points simultaneously in a calm stasis, cosmograms differ by charting action over time and space, sometimes even described by mathematics. This visual agency summarizes a broad sampling of key ideas and metaphoric meanings of West African and Kongo culture, which Thompson has written about extensively, and which appear in the work of Basquiat.

Ethnohistorical sources confirm that this symbol existed in Kongo culture before European contact in the late 15th century (Fennell 31). It diagrams the practice and belief that there are several planes of existence:

The earth is a mountain “over a body of water which is the land of the dead, called Mpemba…where the sun rises and sets just as it does in the land of the living…the water is both a passage and a great barrier. The world, in Kongo thought, is like two mountains opposed at their bases and separated by the ocean.

At the rising and setting of the sun the living and the dead exchange day and night. The setting of the sun signifies man’s death and its rising, his rebirth, or the continuity of his life. Bakongo believe and hold it true that man’s life has no end, that it constitutes a cycle, and death is merely a transition in the process of change” (Janzen 34).

African cosmograms can be fashioned from elements in nature, such as in the form of two crossed sticks in the woods or the intersection of two roads, implying the intersection of two realms. Basquiat used this ancient practice of employing found objects in his own work, painting and drawing on any surface he could find, from brick walls, to concrete, or even a refrigerator door, pulling the street into his practice of making art. In Sub-Saharan African culture cosmograms were carefully drawn in dirt, or painted on the side of a wall or etched into stone, much like current-day graffiti and often represented a specific point of access to spirits of the underworld or the gods.

As the African scholar Fu-Kiau explains, if seen literally as “x” and “y” axes (Fig. 1) a vertical axis exists at their intersection, which provides a conduit to the underworld or to the gods above. Comprised of intersecting vertical and horizontal lines set within a circle, variations may include further intersections or arrows suggesting movement and direction. It might show circles at the end of the intersecting lines to represent the apex of a person’s earthly life opposed to his spiritual plane, and the moving sun, rising and setting throughout his life (Fu-Kiau 25-32). The particularities of this symbol suggest a narrative or three-dimensional blueprint for existence, as Christopher Fennell explores in Crossroads and Cosmologies, where he supports the notion that the persistent appearance of these patterns over time in West African culture can be interpreted with associated meanings.

As a sort of hieroglyphic to explain life’s story, these symbols have been evident in West African and Kongo tribes for centuries and have been elaborated upon, showing more complex intricate patterns or simplified into abbreviated X’s, or even V’s implying an arc of travel or motion. (Fig. 2). “The ‘Vee’ teaches with all simplicity the formation process of the universe” (Fu Kiau 132). Built on an infrastructure using polarity symbols to suggest movement, and opposition, conflict becomes a positive and necessary phenomenon—a colorful, dynamic opportunity for change or healing. Thompson supports this construct by linking African structures to a variety of contemporary black art forms, which include not only visual ones but also music and dance— built on confrontation and resolution. The most important part is the point of intersection, the clash, the butting up against or crossing over. These “signs of reappropriation”[5] are the imaged polemics or intersections—present and past, mundane and spiritual, love and hate, or masculine and feminine. The opposites enhance the strength in each. Pairings like these are the alphabet of Basquiat.

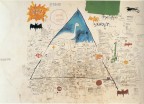

Other forms of Basquiat’s vocabulary will be explored with reference to cosmograms, such as in the complex Carribean cosmogram (Fig. 3) and Untitled (Fig. 4). The hierarchical information displayed in both the Trinidadian diagram and his letters and numbers reflect a compositional similarity, within a set of intersecting triangles making a star shape, a motif seen in a variety sacred practices.

Codifying content in Basquiat’s work is a relevant reference to the cosmogram, and requires deliberate engagement with the viewer. He often crossed words out, emphasizing them by hiding them, which further created mystique. Using the copyright symbol after his name SAMO© or his ubiquitous crown signature was another form of imposing a new identity or value to his subjects.

More discussion will be devoted to Basquiat’s fascination with letters and numbers, such as the letter A and what it represents in his paintings, and how it is used as a structural device. [6] The letter becomes the subject, as in Cadillac Moon, 1981 (Fig. 5), where the letter A is repeated over and over, creating its own shape. The letter is thought to refer to the double A’s

in Hank Aaron’s name, a theme he returns to repeatedly in his work, elevating the names of black heroes and athletes to iconographic status.[7] Hank Aaron was one among many of his inspirations, struggling within the constraint of a white world. In Cadillac Moon, we also see a crossroads, with a cartoonish stack of T.V. sets on the right hand side of the work. Two cars areindicated, one at the top and the one at the bottom, dismantled from its chassis, most likely

referring to a life-changing car accident resulting in a bedridden recovery from losing his spleen. The ambulance is apparent in Untitled, 1981 (Fig. 6) as well, with an array of A’s creating patterns with O’s of the wheels. The hammer and nails suggests another kind of collision and the planes are flying in two different levels of the sky. Often in Basquiat’s earlier drawings, we see a double plane or a car, one on top of the other as we see here in these two drawings of planes and cars, depicting two realms simultaneously occupied. The cannon and hammer both suggest an explosion, the breaking of a sound barrier perhaps.

Dismantlement and anatomy[8] recur time and again in his work along with the theme of collision, whether with cars, fistfights, or boxers, and indicate a kind of transformation through clashing. Again, the point of intersection is the point of change in the cosmogram and so it is in Basquiat’s work, the ambulance appearing between the two planes as healing resolution for collision. Other symbols of heroism, such as the bats in Untitled (Fig. 4) with the balloon burst with “hey” inside it suggest the cartoon hero of Batman. For other heroes, like jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker, he created a matrix with words in Tuxedo, 1983 (Fig. 7 and 8). The tuxedo jacket shaped by the words themselves provide an interesting metaphor for the status of the great music legend. We can see several cosomogram images within, one in the form of a circle with two perpendicular arrows through the center of the work, like a central compass rose in the place where the man’s heart would be. Another circle with curvy radiating spokes can be seen on the left, with “Sun King” written inside, a divine nametag. Another to the lower right looks like a medal with ice melting from it on the bottom, and inside it reads “Blue Ribbon,” another measure

of quality or status, that can so easily change or melt away. Charlie Parker and Bebop music were inspirations that Basquiat pictorialized over and over.

Opposition and Polarity

Several examples will demonstrate polarity, as in the cosmogram, an intersection of opposing forces in Basquiat’s paintings. The place where these forces meet is the exact locus where opportunity or action happens, to express his masculinity and his identity as a son and a man of color in the art world of the ‘80s. African art historian Andrea Frohne points out hunting symbols in Basquiat’s paintings that she believes he may have borrowed from images in Thompson’s Flash of the Spirit, strikingly similar to the Yoruban drawings of the hunter spirit Oshoosi and the trickster Exu, complete with bows and arrows. Her argument is compelling, not least because it accounts for his fight to acquire a firm position in the 80s art scene of New York. An Oshosi song lyric of the powerful child “becomes famous and fame becomes power” (Frohne 439) seems prescient regarding his career, and gives new meaning, for example, to the figures in Self-Portrait (Fig. 9 and 10). They are black warriors, much like the rock paintings mentioned with outstretched arms almost perpendicular to their vertical bodies, a layout we often see in renderings of male figures. The vector of the man’s arm in the painting on the left is punching towards two o’clock, rising up the air in defiance or pride, holding an arrow perpendicular to his arm. These angles are reminiscent of the kind of grid and geometry we see over and over in cosmograms. The figure on the right is almost his own cosmogram, a vertical body and arms at 90° to his body, pointing east and west with knife and mallet in each hand. In the thesis, we will see in other portraits where Basquiat often uses the head and body as a cosmogram matrix or grid, intersecting lines within a circle.

Action and Migration

Agency expressed in aggressive paint strokes and vibrancy of pigment is a powerful reminder of West African ritual where music, dance, theater, and physical objects are often incorporated in performance, action and connection. The esteemed anthropologist and Harlem Renaissance author Zora Neale Hurston describes what she called Negro expression in 1934:

“His very words are action words. His interpretation of the English language is in terms of pictures… the speaker has in his mind the picture of the object in use. Action. Everything illustrated. So we can say the white man thinks in written language and the Negro thinks in hieroglyphics (Hurston 355) …”

Her observation is relevant to Basquiat fifty years later and is fully supported in the body of work to be discussed; it directly relates to the matrix of the cosmogram in its expressions of action, doing, and collision.

In Six Crimées (Fig.11), we see six figures with circles above their heads, with protruding lines, like halos or thorns.[9] The grids below them resemble the geometry seen in cosmogram line work and crossroads, but more likely relate to dice games or chalk on a sidewalk in urban New York, or possible the grid of the city itself. Triptychs are common forms for Basquiat, compartmentalizing and repeating his objects, for emphasis, much like Haitian motifs.

Movement takes on another dimension in his work when we see King Alphonso (Fig. 12). Here is a distinct example of the cosmogram plainly in view, acting like the head of an arrow on the right side of the canvas. The vector shape moving from left to right in the center of the image dissects the head with what looks like a bullet or arrow. The trajectory of the vector is delineated by solid and

dashed lines, a spiral coming from the left of the skull shape. A clearly fashioned cosmogram, a circle with an X through it, sits on the right of the image with the arrow moving through its center. A number of scribbles add to the drawing of lines and angles coming out of the diagram, which centers on a bright red head, a black mouth and blue nose. Grids and checkerboards provide a schema for might be called the area of the brain of this head, suggesting processing and complex thinking. Sitting atop this head is a black curly hair and a big black crown, drawn boldly in seven thick lines, the signature that appears many times in Basquiat’s work. Also notable about this image is the lack of color, except for the head. Nearly an entirely black and white drawing, the red head takes up merely an eighth of the canvas, but because of its color we are drawn to its sanguine nature. The face looks angry, braced for something, with gritted teeth and fixed eyes. The title scribbled below, “King Alphonso,” another name with an “A,” likely refers to Hank Aaron or to Nzinga Mbemba (c.1456–1542). Otherwise known as King Alfonso I, he ruled the Kingdom of Kongo in the first half of the 16th century and was best known for converting Kongo to Catholicism, merging tribal spiritual customs with Christianity. Many Kongolese challenged his controversial liaisons with Portugal, including his half-brother, with whom he went to war. His legacy, however, includes his emphasis on modern innovation, which helped modernize Kongo’s school system: a positive outcome from conflict. The technical diagram aspect of King Alphonso suggests a transition, a measure of velocity from one place to another.

The action in King Alphonso also brings to mindthe speed and accuracy of sports, not to mention another “Alphonso.” A current baseball favorite, second baseman Alphonso Soriano signed with the Yankees in 1998, tens years after Basquiat died. Often compared to Hank Aaron, the Dominican Soriano is a strikingly thin and powerful hitter.

The picture is made of angles and triangles, with a clear sense of movement, as if the baseball is moving precisely through the subject’s eyes towards the cosmogram, the ultimate target. The angles on the sides of the head give the impression of tension springing upwards, like a scissors jack. With an efficiency of linework and color, we experience a powerful dynamism in King Alphonso, a clear sense of movement and agency.

Transliminality and Transcendence

“What identifies Jean-Michel Basquiat as a major artist is courage and full powers of self-transformation. That courage, meaning not being afraid to fail, transforms paralyzingly self-conscious predicaments of culture into confident ecstasies of cultures

recombined. He had the guts, what is more, to confront New York art challenge number one: can you transform self and heritage into something new and named? (“Royalty, Heroism, and the Streets” 36)

Revisiting Tuxedo we also see the concept of changing states, evident in almost indistinguishable scribblings of text— with arrows and equations, signifying one thing equaling another, or something transforming with a particular function applied to it. His later work The Melting Point of Ice refers to this phenomenon as well. What exactly determines the moment a person can actually change becomes a question Basquiat explores again and again, such as the tipping point of one remaining cool versus losing one’s temper. The tension of pushing back, acting out against, or holding multiple conflicts simultanoeously, recurs repeatedly.

The nature of transcendence or transition in Basquiat’s work, ways that he expresses separate realms and the connections between them, those inks between two worlds, brings to mind W.E. B. Dubois’ often cited term, “double consciousness.” The term describes the nature of the black person who has been dislocated to America and how he experiences two states of being. Seeing oneself through the “revelation of the other world” or “looking at one’s self through the eyes of others” (Du Bois) is yet another kind of intersection, the focus being where two forces meet. Like the spark flashing in the gap between two charged poles, this sacred locus is a chance for the unseen to work its power, for the material plane to cross with other realms, perhaps another

perspective or a spiritual state. This ability to hold the present and the past in a work of art is precisely the message of Basquiat, building upon ancient visual architecture, and allowing for two opposing ideas or constructs to clash. In this way, conflict is important, a chance for growth. The symbol of the ambulance is a healing one; the warrior is a protector and the crown an overarching halo of value and the copyright symbol legitimacy.

A New Kind of Africanism in the Twentieth Century

African influence in Modern art has been widely discussed since the beginning of the twentieth century. Picasso and Braque shared an appreciation of African imagery and Cubists openly described their works as inspired by African masks and sculptures. But Cubism was often more formal than narrative: deconstructing objects and figures into simple planes and forms, which led to labeling Primitivism as a movement in Modernism, expressing mere suggestions of Man’s natural form and gesture via an intellectual and analytic approach. Deviating from romantic or spiritual themes, previously popular throughout European works of the nineteenth century, Cubism was not a movement of cultural narrative. Formally dissecting exotic images is the very reason

that contemporaneous black artists were not inclined toward this pursuit; the common denominator in Black Atlantic artwork is not intellectual abstraction, but a need to tell a story.

This narrative of polarity is often expressed through two-toned or clashing shapes; during the Harlem Renaissance, the work of artists such as Jacob Lawrence or Aaron Douglas feature jagged compositions expressing dynamism, conflict, or frustration. More contemporary artists such as John T. Biggers used bright colors reminiscent of the West African and Kongo palette.

In the last three decades, we have seen a different influence of West African imagery emerging, a rougher presentation of found objects, mundane street imagery, and scrawled text. This more “primitive” presentation has gained a certain acceptance in the art

world, possibly because of its chronological distance from the Black Diaspora, and an evolutionary advantage following Abstract Expressionism and Conceptualism. Perhaps “high art” can finally embrace African forms without condescending to calling it naïve. We experienced the raw form of Matisse almost a century ago, an artist who Henry Miller describes as having the “courage to sacrifice an harmonious line in order to detect the rhythm and murmur of the blood” (Miller 164) the wild colors agitating his viewers as well as his subjects. Joseph Cornell’s conceptual work from the mid-twentieth century, influenced by Surrealism, used quotidian elements and found objects to create icons and transform

“primitive” constructions into shrines. But here we are invited to experience the ancestral intention of these symbols, not abstracted or deconstructed “primitivism” as a means to a new end. Rather, in the work of Basquiat, we experience a compulsion to use the very symbols used in the African visual lexicon to create work closer to its roots, with original intention and meaning or at least bridging one context to another. Often mystical or enigmatic, these symbols are reminiscent of cosmograms in their ability to do just that.

As a conclusion to my analysis, I will broaden my observation to include Basquiat’s legacy, and demonstrate his influence on later artists. By using the example of the work of John T. Biggers, Renée Stout, and Keith Piper I will show how they have incorporated the ideology of the cosmogram into their work in ways quite different from Basquiat.

© Lisa Clark April, 2013 All information in this blog is copyright to the original author, from whom nothing can be copied without written consent. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

Hi Lisa,

Just wanted to say thank you for this article. I’m using JMB as inspiration for an assignment at university and this has helped immensely. So interesting to read what you have to say, it’s so different from anything else I have found on this amazing artist.

Kind regards,

Laura

Hello Lisa,

I enjoyed reading your review of Basquiat’s work. Your insights are great and make sense. I would like to mention that in the painting King Alphonso it is very unlikely that Basquiat refers to Alfonso Soriano of the Yankees. The painting was completed somewhere between ’82-’83 and Soriano was born in ’76. He signed with the Yankees in ’98, 10 years after Basquiat’s death.

I do, however, think King Alphonso is supposed to be Nzinga Mbemba (c.1456–1542) ( or King Afonso I ), ruler of the Kingdom of Kongo in the first half of the 16th century. He added the name Afonso after converting to Christianity, when the Portuguese arrived in Kongo for the first time. He had ties with the Portuguese King at the time, but was totally against the slave trade.

This is who I think King Alphonso (or Afonso) might be. Let me know what you think!

Sincerely,

Jacob

Deeply referenced and informative, I find your desire to link Africa and the USA too easy and therefore falls in the trap of comfort. There is too heavy an emphasis on the symbolisms from Africa and assumption that the meanings are transferred without morphology onto his work. How? By his just being black? Did he travel? What books did he read?

Underlying your writing is the idea Basquiat as the vessel of Africa meets black American and pours forth in his work. Your denial (exclusion) of his Haitian heritage means you did not understand that he quite possibly didn’t need to adopt or create new lexicon, the symbols were already part of his heritage. To write about Basquiat and Transcendence and not reference the morphology of West African symbols and practices as they are understood in Haiti and then migrated to the US, is to ignore a significant part of his particular experience that made him unique when compared to other artists and uniquely expressive.

Hi June, I just saw this post. Thanks for responding.

Here are my thoughts, as I read your post. I wasn’t as interested in how African symbols and practices are understood in Haiti, as much as Basquiat’s interest in their roots in Africa, and what that meant to him and his work.

Basquiat was indeed a student and scholar. He read “Flash of the Spirit” among other books by Robert Farris Thompson, befriended the author, and had an extensive library of African imagery and art books. He was a jazz aficionado, had many biographies of jazz musicians in his library, along with American, European and African history books and an extensive record collection. He traveled to Africa later in his life, to Abidjan, Ivory Coast.

He was half Haitian but raised mainly in Brooklyn with a brief stint in Haiti as a child.

I don’t think I conveyed here that he created new symbols; the symbols, particularly the cosmogram, remain timeless. What I am saying is that he used these symbols to convey his personal editorial, his lexicon, on Black American history and to express a reverence for his roots in Africa, via Haiti, or Puerto Rico, where his mother was from.

His interest in conflict and transcendence, represented by the cosmogram worked beautifully to achieve his often angry message, both aesthetically and philosophically. The meaning of the cosmogram has not gone through a morphology so much, as it is a sacred 16th century symbol, representing an approach to living a life: including government, community and spirituality. Whatever morphology he intended was his own, not based in Haitian culture as much as his own culture, of a displaced Haitian/PuertoRican American in lower Manhattan in the 80s.

Hi Lisa, thank you so much for such cleaver well informed article on Basquiat’s ancient kongolese roots! I am Brazil’s first black femae filmmaker but so far nobody has written about my work. If possible, I’d like for you to see and perhaps comment on my film A FUNERAL AT THE SAMBA SCHOOL (2000), which uses the dikenga cosmogram and cromatic symbolism as part of the filmic narrative. Soncerely, DAN

I have an 1981/1982 Important Powerful Cosmogram by Basquiat I would like to send you an Image of.

Sure. Thank you.

1982Who else but Basquiat would have done this Cosmogram? I bought this 5 Years ago now. What does the 44 mean?

Nothing attached. Without seeing your image, I can say 44 is Hank Aaron’s jersey number.

Hank Aaron, or Hammerin’ Hank, remains baseball’s all-time leader in RBI (2,297) and total bases (6,856). Basquiat was in awe of him. Hero worship.

He often depicted hammers, or many AAAAAA’s in his paintings.

Hi Lisa, I’ve been researching on this as well and have noticed similarities with the Kongo cosmogram within Basquiat’s ‘Bird on Money’. The references to death, the symbolism of water, the ‘leaves’ in every season’s quadrant except winter (and they are falling in the fall quadrant), the bird being in both the spiritual and physical world, etc… There are many commonalities but I’m not sure if it’s enough evidence to create a definite link. I urge you to take a closer look as I would love a second opinion. Thanks for this great article as it has been a great help in my work! 🙂